hi there!

I’m so glad you’re here with me today to learn about the medieval world — and hopefully, to do a little reflection on yourself as well. Today, we’re doing two things:

- First, we’re going to learn a little about Hildegard of Bingen, a medieval nun, and the music she wrote.

- Then, we’re going to listen to a little bit of her music.

- Next, we’ll learn about the kind of music she wrote and how to read it.

- Then, we’ll try to sing just the first few notes of the piece we heard.

- Finally, we’ll think about how that made us feel.

Every activity from In Every Sense focuses on one or more specific sensory experiences — this one mostly deals with sound, but since we’ll be using our mouths and vocal cords to sing, this activity will also kinesthetic as we use our bodies. In fact, even if you don’t like singing, you can pay special attentions to the vibrations that singing creates.

If that sounds good to you, let’s dive in.

A small and gentle reminder: as always, these activities are more about how the act of creation makes you feel and less about the thing you’re making. Together, let’s try to focus more on the act of creating something new and less about whether or not it sounds “good” or “right.”

part 1: learn a little

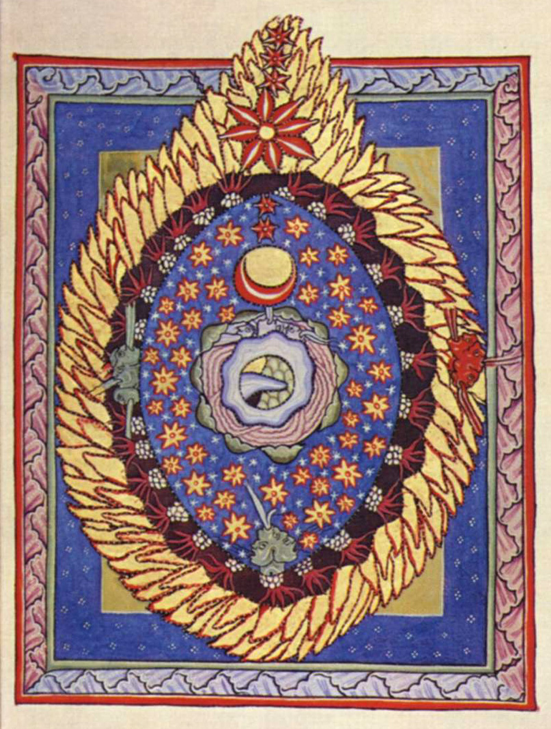

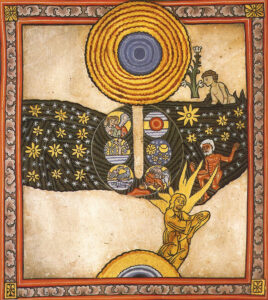

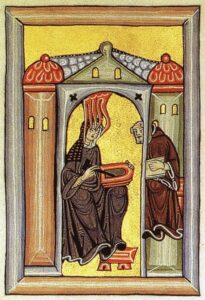

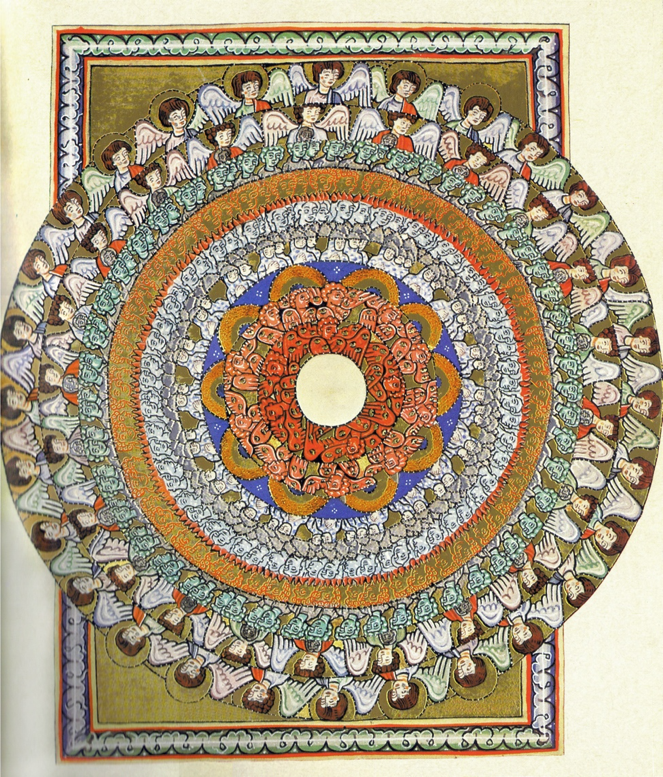

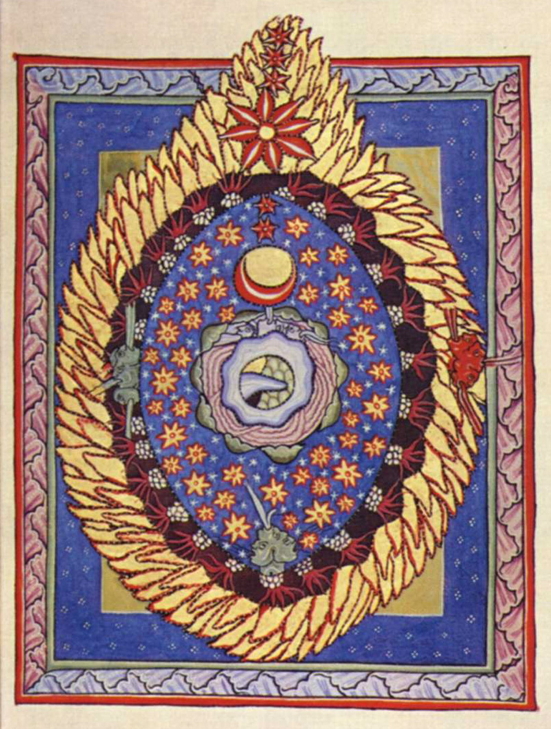

If you’ve done some of the other activities on the site, you might be familiar with Hildegard of Bingen and her book, Scivias, already. Neat! You might already know some of what’s written below, but in this activity, we’ll explore a little bit more about Hildegard’s music, something we haven’t talked a lot about yet.

Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179) was a prominent nun and abbess in what is now Germany. She might be well known today for some of her theological writings, but she is also one of the most prolific named composers of the Middle Ages — we have a vast amount of her work still surviving today, and in fact, her musical play, the Ordo Virtutum, is the earliest surviving complete musical morality play. The Ordo Virtutum depicts a lot of the ideas and events of her most well-known book, Scivias, and many of the songs of the Ordo Virtutum come out of the text of Scivias. She also wrote a great deal of liturgical music — music that would be sung in church services.

One of those liturgical pieces is an antiphon (a short musical response) called O virtus sapientiae — commonly translated as “O strength of wisdom,” although the word virtus (from which we get words like virtue and virile) can mean a lot of things, like “power,” “bravery,” and “worthiness.” I think that “strength” gets the point across pretty well, though. That’s what we’ll be looking at today, and of which we’ll be learning to sing the first few notes.

part 2: listen a little

There’s a lot of great recordings online of this piece you can hear, but I’ve chosen this one because the YouTube channel it’s on is named after Hildegard, and I love a good pun (the channel is called “Hildegard von Blingin'” which makes me laugh a lot). It’s quite short, so take a listen if you can.

Pretty neat, right! Ready to sing the first few notes together, reading the music the way Hildegard would have? Let’s go.

part 3: learn a little more

Now, the issue is that musical notation was super different back in Hildegard’s day than it is today. Most notably, there were no notations for tempo or rhythm. This special kind of notation is called neume, and you’ll almost only see it used in very old pieces of music like Hildegard’s. The music that Hildegard wrote, using neume, is called plainchant or plainsong. Let’s take a look at what a modern, standardized version of this would look like (so, it’s been cleaned up for ease of reading — this is not a picture from a medieval book).

Oh boy. What the heck is that?

Don’t panic. We’ll learn it together. It’s not so hard as you think!

First, The big letter O there is just a fancy way of writing the lyrics down, as this is the first word in this song. In fact, this is the O that starts O virtus sapientiae!

The two little nubbins next to that O are the clef, to tell us where the scale starts. Normally, the clef would tell us the key of a piece of music, but plainchant isn’t in any particular “key” though, as it doesn’t use fixed pitch (so, A doesn’t always have to sound like 440 Hz). That makes our job really easy. You can start on whatever note you like, honestly, as long as you move up and down the right number of steps. (This is using the solfege system, which sounds scary if you don’t know it, but if you’ve ever seen The Sound of Music and you know the “Do Re Mi” song, you know solfege. All those two little nubbins do is tell us where “do” is.) Neat! For the sake of clarity here, though, I’ll be using the modern key of C. You can take a look below at the letter O and the two nubbins that make the clef.

Now we’re at the first few notes, which look like a weird wonky flag or something. It’s not a weird wonky flag, though. Those are four separate notes. Now, all these funky notes have fancy names that you don’t particularly need to learn. The first note is the bottom-most and leftmost nubbin. The line that connects it up to the thing I think looks like a flag just tells us that we’re singing the next note next. Easy. The second note is actually the left-hand side of the flag thing. Then the third note is the right-hand side of the flag — when the flag slides down from the space to the line, that’s a different note. Then the fourth note is the little nubbin on top of the third note. If that made no sense at all, there’s a picture below where I’ve marked and numbered the notes.

Whew. That was a lot. That whole configuration of notes has a name — it’s called a porrectus — and it just tells us that we’re going up, then we’re going down, then we’re going up again. We can do that. Up a lot, down a little, and then right back up a little. In solfege, that’s mi, ti, la, ti.

Now, it’s actually pretty straightforward from here. The next thing we see is a big waterfall of notes going down. And that’s really all it is — we’re just going to start at that top note and sing six notes going straight down in a scale — mi, re, do, ti, la, sol. You can see our little waterfall below.

When we get to the bottom, we see the same note three times in a row. Now, as best we can tell (because of course, we don’t have any recordings from the Middle Ages!), we think that used to just mean you hold that note longer, like three beats. So we’ll do that. Take a look below, if you’re using pictures to follow along.

Then we jump up high again using that little line we saw before. But we know what that means now! We’re old pros at following that line up to the top. So we will, and then we’ll sing down our little scale again, but just lower this time. Do, ti, la, sol, fa, mi. Again, if you’re following along, take a look at the picture so you know where we are.

Look at that! We reached the end! That wasn’t so scary after all. And if it still makes very little sense, that’s OK. I’ve been reading neume for a long time, and my brain still goes blank a little bit the first time I look at a new piece of plainsong. It looks scary! But it follows rules that aren’t that hard to learn, and now you’ve learned some of them. Great job.

Now that you’ve done that, you can take a look at what the music would look like if I transcribed it into normal modern notation.

OK, that’s significantly less scary. If you were lost throughout all the neume portion, we’re back in the land of modernity and non-scariness. You might see plainchant noted like this if it’s not meant for a musical group to sing — but hey, we notice that all the notes are the same length. Well, like we learned earlier, the notes in neume don’t have a specific length noted, so you can sort of do what feels best for you. Sound good?

Below, I’ve attached a recording of how just the part we learned sounds, without any words. I’ve used my own interpretation of note lengths, inspired by the recording we listened to earlier. Take a listen.

part 4: sing a little

Do you feel like you’re ready to sing it? You can sing it in whatever octave you like, and starting on whatever note you like if it feels too low or too high. You can just sing it on “O,” since that’s what Hildegard wrote, or any other sound you like. Maybe you can make up your own words to these notes! (And if you do, I’d love to read them! Send them my way.)

If you don’t like singing, or you don’t think you’re very good at it, this might feel a hair daunting. That’s OK. I suggest taking time to feel how it feels in your body to sing these notes. You can put your hand on your chest or your neck or your jaw and feel how your vocal cords and face and breath move as you sing it, and make it less about how it sounds.

When you’re rather bored with singing this, come back, and we’ll talk about it a little.

part 5: think about it a little

How did that feel? It might have been a little weird. But on the other hand, you might have found it fun, and a little relaxing.

I picked this line for a reason, and that’s the two little fun repetitive “waterfall” scales. See, a lot of Hildegard’s music has these big repetitive lines and elements. There’s a lot of music theory research that’s been done on this, and some scholars think that those repetitive elements might have served as a way to meditate on things as you sang — like with some of the other activities we’ve done here, you could sort of let yourself get lost in the act of making something (in this case, making music) and do some thinking (and Margot Fassler has a great chapter on this in a book called Voice of the Living Light, which you can learn more about in the bibliography for this site).

Maybe you sing this line a few more times and try to do some thinking while you sing. Maybe you’re tired of singing, but you might want to go back up to the YouTube video I shared and listen through it a few more times while you think. Maybe you’d like to listen to more of Hildegard’s music, of which there is no shortage online and elsewhere, while you think. Do the repetitive bits give you a little more clarity? They do for me, and they very well might for you, too. Try it out — and know that while you do this, you take part in a tradition of singing these songs that reaches back nearly a thousand years. That’s pretty neat.

Thanks for spending time today with me, with Hildegard, and most of all, with yourself. I’ll see you next time.

P.S. If you want to tell me how you felt about doing this activity, you can drop me a line here.