hi there!

I’m so glad you’re here with me today to learn about the medieval world — and hopefully, to take a little time for yourself. Today, we’re doing two things:

- First, we’re going to learn a little about Hildegard of Bingen, a medieval nun, and her work.

- Next, I’ll give you some coloring book pages to download based on her art — and you can color them!

Every activity from In Every Sense focuses on one or more specific sensory experiences — this one mostly deals with sight and vision, but we’re also going to be making art of our own, which is kinesthetic since we’ll be moving our hands and bodies to do so. You can even vary the level of touch involved in this project — while the examples here will mostly be geared towards coloring on printed-out paper, you can color digitally by uploading the images into your favorite digital drawing program. In fact, at the end, you can choose between a JPEG file that’s best for printing or a transparent PNG file that you can upload into such a program.

If that sounds good to you, let’s dive in.

A small and gentle reminder: as always, these activities are more about how the act of creation makes you feel and less about the thing you’re making. Together, let’s try to focus more on the act of creating something new and less about whether or not it looks “good” or “right.”

part 1: learn a little

If you’ve done some of the other activities on the site, you might be familiar with Hildegard of Bingen and her book, Scivias, already. Neat! You might already know some of what’s written below, but in this activity, we’ll explore a little bit more about the history of the different manuscripts of Scivias through the centuries.

We might be able to call Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179) a “Renaissance woman” if it were not for the fact that she lived two hundred or so years before the start of the Renaissance — she did an awful lot of different things. Not only was Hildegard a very important nun and abbess in her area, founding two new monastic communities in her lifetime, she was also a writer, a composer, a linguist, and a practitioner of herbal and traditional folk medicine.

Perhaps her most famous work is Scivias, a book of religious visions she said she received from God over her lifetime. Scivias was written down in a number of manuscripts that are all beautifully illustrated and gilded. The most well-preserved one was called the Rupertsberg Codex, but unfortunately it was lost in World War II, having survived since around the time of Hildegard’s death. The good news is that there were a number of black-and-white photographs of it taken before its disappearance, and there is a facsimile (made with traditional methods) that resides in Eibingen, the modern site of Hildegard’s abbey. Some of these images are in the public domain, and some are not, which makes our work a little difficult, especially since a good facsimile of a medieval manuscript can cost thousands if not tens of thousands of dollars — and Scivias is no exception to that.

So, how were the manuscripts of Scivias made? And were the nuns at Hildegard’s abbey involved? These are some pretty big questions, but I think they’re worth digging in to. We know that religious and monastic women were doing an awful lot of art at this time in history and in this part of the world especially, but it’s hard to say how much they would have been involved in manuscript production. However, there’s one interesting case study that might be worth thinking about when we wonder about women’s involvement in manuscript production.

A few years ago, anthropologists found a skeleton of a woman, buried near a monastery in Germany, who had traces of lapis lazuli in her teeth. Lapis lazuli was at the time the fanciest way of making blue pigment, which was already pretty fancy on its own. So, this was a really expensive pigment — why did this woman have it in her teeth? One theory is that she was involved in the painting of some really expensive and really beautiful manuscripts, and that she used her mouth to moisten and sharpen the point of her paintbrush (a trick we know people were using in the Middle Ages). And we get the evidence that women could have been involved in doing some of this highly skilled and expensive manuscript work because of a manuscript of Scivias which both contains this pigment and was probably made by a woman at Rupertsberg, one of Hildegard’s abbeys. If you want to read more about this, there’s a full citation for this article, which came out in 2019, in the site bibliography here. But I think it’s pretty interesting to imagine women in these monastic communities having access to some really fancy and valuable materials with which to do this important work — and it makes me wonder how those women felt about doing this work. Personally, I’m always excited when I get to work with fancy art supplies, and none of mine are nearly as fancy as lapis lazuli. Maybe, when coloring these pages, you can break out some of your fanciest art supplies and see how it feels to you. Is it more special? Do you pay a little more attention? Do you get into it a little bit more? You might want to keep that in mind as you color — but honestly, I think these coloring book pages are just for fun, and I just used plain old crayons and markers on mine.

part 2: make some art

In the spirit of making Scivias available for everyone (since it’s so hard to get our hands on one of those expensive fancy reproductions) and still thinking about how making art makes us feel, then, here are four coloring book pages of some of my favorite illustrations from Scivias. There’s no prompt here for how to go about coloring them in — you should do what feels right to you, I think. This activity is less about learning something about yourself and more about relaxing and taking some time for yourself, but that can be a way of learning and looking inward as well. Maybe you can take some time to think about how this time for yourself makes you feel — or maybe you’ll just have fun for a little while. Either way is good!

In the interest of letting your creativity run wild (and based on some suggestions I’ve heard), you might not want to see what the real colors of each illustration are before you color them in — I’ve hidden them behind buttons below, though, so that if you want to see them, you can.

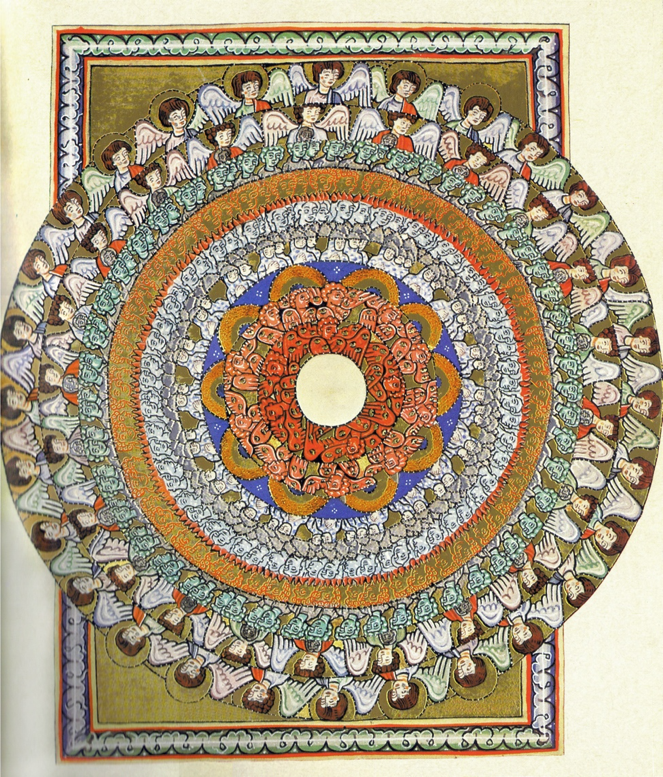

The “Fall” page is based on Hildegard’s image of the fall of the angels from Heaven.

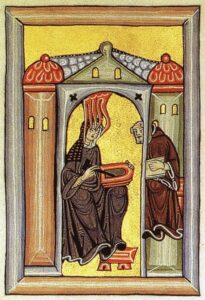

The “Visions” page is based on a portrait of Hildegard as she received her visions and wrote them down.

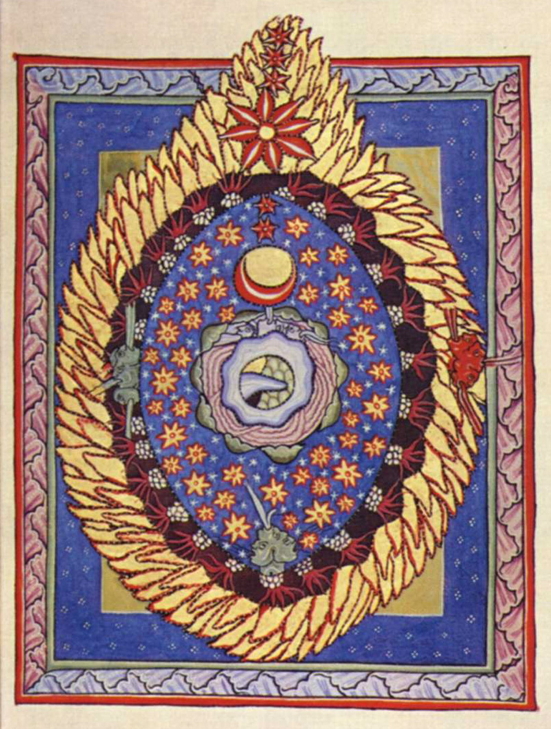

The “Creation Days” page is based on a larger illustration called “The Redeemer,” but focuses in on a specific part of the image depicting the six days of creation detailed in the Abrahamic tradition.

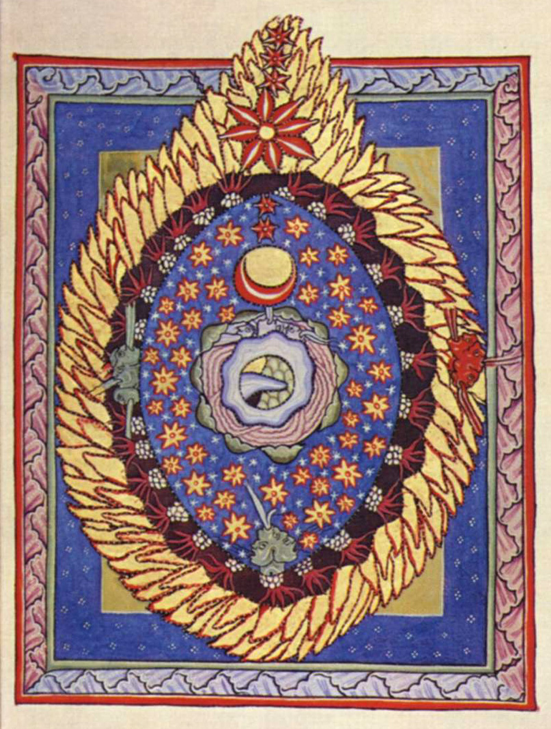

The “Cosmic Egg” page is based on an image that you’ll probably have seen elsewhere on this site, depicting the beginnings of the universe.

Thanks for spending time today with me, with Hildegard, and most of all, with yourself. I’ll see you next time.

If you tried out this activity, we’d love to see how it went. Click here to submit your art to our gallery. And if you want to take a look at what some other people have made doing this activity, click here to see our gallery.

P.S. If you’re intrigued by Hildegard’s images, check out the Cosmic Embroidery and Creation Mandalas activities. And if you want to learn more about my research into how religious women in the Middle Ages felt about their art, click here.